Kurt is the COO of an innovative non-profit that marshals corporate resources to address problems in its greater municipal area — education, pollution, transportation etc. Business is good for Kurt, and opportunities abound. He’s been to Shanghai twice in the past year to coordinate with businesses there; he’s leading an exciting new cyber-security initiative between government and industry; he’s involved with an program to improve outreach to existing member corporations; and he’s leading the charge to recruit new corporate members.

There’s only one problem: corporate membership is down. Attrition is high, because member companies feel that they don’t get enough attention. In fact, it’s only increased since the non-profit started pursuing some of its new programs. Which is sort of like saying that your bank does a great job of providing free wi-fi and donuts in the lobby, but it has an unfortunate tendency to lose track of your money.

You see this problem all the time. Companies can’t execute on the simplest and most critical tasks, because they’re trying to do everything. They pour resources into entering a new market but neglect their existing customers. They develop sexy new products but forget to update and improve their current products. Individuals do the same thing: they take on high-profile new projects but stop attending to their existing responsibilities. Reach > grasp.

Jeffrey Pfeffer, professor at Stanford University’s business school, tells this story:

Gary Loveman, CEO of Harrah’s Entertainment, is someone who gets this. Visiting Stanford one day, he told my class that when he entered the company as COO he reduced most executives’ job scope, because he believes that people don’t do very well processing complex agendas and that success mostly comes from effort focused on the most critical and achievable objectives.

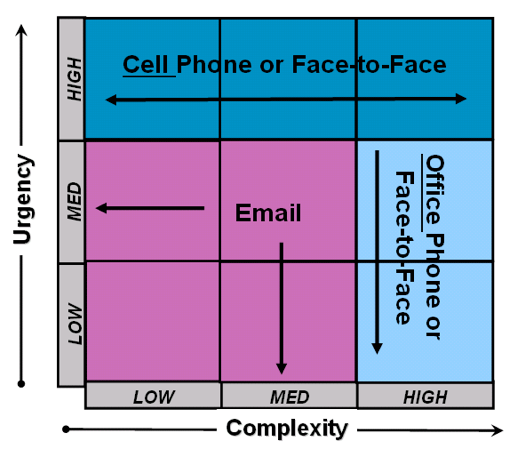

Your most limited resource isn’t money. It’s time and mental focus. Not only are there a finite number of hours in a day, there’s a finite amount of processing and decision-making power in a day. As an individual, that means that you’ve got to ruthlessly prioritize the areas in which to pour your attention. As a leader, that means that you must constrain the job scope of each person on your team, like Gary Loveman.

Kurt isn’t to blame for the high attrition rate at his non-profit. It’s his CEO’s fault. He’s a brilliant thinker who discovers opportunities all the time. . . and then dumps responsibility for executing them upon Kurt. Without the discipline to say no to some of them, or the willingness to match managerial resources to his agenda, the CEO is dooming the organization to a future of unrealized expectations, half-baked initiatives, and a declining membership.

Limits are real. Acknowledging them is not a sign of weakness or timidity. It’s a sign of pragmatism that will help you get to where you want to go.

Download PDF

Download PDF